Why These Two Unconventional Farmers are Turning Heads in Iowa

Wild, unconventional, early adopters. It’s not uncommon for Nate Huntley or Josh Nelson to turn a few heads in Wright County, Iowa. The two young men who farm on opposite sides of the county met five years ago when they were elected to the Wright County Soil and Water Conservation District. They quickly realized they had a lot in common — not only did their daughters attend the same dance studio, but they both raise pigs for Smithfield Foods and are passionate about sustainable farming. Although their journeys to become farmers are quite different, both are rising as leaders in sustainable farming practices.

The Huntley family has seen a significant drop in fuel usage and carbon emissions since implementing sustainable farming practices. Photo by Lori Hays.

AN EYE-OPENING EXPERIENCE

Growing up on a family-owned farm, Huntley went to Iowa State University to pursue a degree. However, partway into his animal science degree, his grandpa was no longer able to do as much on the farm, so Huntley returned home to help the family.

“I was happy to come home to farm. It’s all I’ve ever wanted to do,” Huntley says. “But we didn’t farm enough to support all of us, so I began selling seed. A few years later, I was approached to sell some of our ground for a company to build a hog building. I decided I should do that as my other job.”

About a decade ago, Huntley began finishing contract hogs for Smithfield, and over time, the operation grew to add another building. Today, he feeds about 8,800 head

on two sites.

During this time, he met his future wife, Olivia, and her dad, Wayne Watts. Huntley recalls finishing combining at his farm and going over to help run Wayne’s strip-till bar.

“At the time, I didn’t even know what that was — he was putting fertilizer in a row in a strip and planting into it,” Huntley explains. “Meanwhile, my dad was running our tractor and ripper. We could see fuel usage and acres per hour with the technology in the tractors. My dad was running half the acres per hour and using double the fuel.”

Neither one could believe it, Huntley adds. His family was paying someone to apply their fertilizer as well, while Watts put on his own. Because he was ripping, Watts would plant right into those strips while the Huntleys had to run the field cultivator.

“Those were the logistical savings of the changes between our practices,” Huntley says. “We weren’t even looking at the impact. We were just thinking: ‘Let’s look at this way to farm because it’s cheaper.’ We weren’t considering the sustainable farming angle and how it would impact the soil.

“Wayne told me, when our soil changes, we will get more earthworms in the soil, which will change our soil fertility levels. We got told those things, but again, we weren’t thinking about soil erosion and water quality. We were simply thinking about the cost savings.”

But as Watts began explaining the “why” behind his practices, Huntley says his eyes were opened. He started going to meetings and learning more about sustainable farming practices.

Photo by Dee Huntley.

A NEW PERSPECTIVE

Nelson grew up on a family farm producing corn and soybeans. He also attended Iowa State University, pursuing a degree in journalism. He spent his first 10-plus years out of college working at newspapers in Waterloo, Iowa; Ames, Iowa; and Springfield, Mo.

“Given my background, however, everything always came back to the farm for me,” Nelson says. “I think my journalism degree gave me the flexibility to look at issues differently or to take advice a little better.”

Maybe that’s why his eyes were opened to new concepts and farming practices as he drove across the state of Missouri in his job.

“So much of what they do, especially if you farm, is connected to the environment because they’re in marginal land,” Nelson says. “It’s an environmentally sensitive area with many things you can do that will immediately impact your operation.”

He eventually got the bug to move home to farm and couldn’t get those ideas out of his head. He wanted to farm in a more holistic manner, but it wasn’t going to be easy. Ten years ago, he got the chance to rent his first field, and that fall, he planted a cover crop.

“I haven’t looked back since,” Nelson says. “As I got more confident in my management practices, I saw the benefits of what those practices were bringing to the soil, to my bottom line and to my budget. You start learning this is all encompassing — it affects everything else.”

In addition to farming, Nelson started raising and selling his own cover crop seed. He says he is trying to find varieties of seed that are better adapted for northern Iowa.

Nate Huntley (left) and Josh Nelson (right) have forged a friendship over the years that centers on their passion to farm more sustainably for the benefit of future generations. Photo by Lori Hays.

TAKE A RISK

Being willing to take a risk and try new things is half the battle, Huntley says. Some of the biggest changes they made to their farming practices were planting cover crops, switching to no-till soybeans and incorporating new manure application methods. Along the way, some attempts were a success.

“We started with some manure application methods that didn’t work with strip-till or no-till, but it was too rough,” he says. “We had to work the ground in the fall after application and again in the spring, so we wanted to get away from that because we weren’t doing that on any other ground.”

They switched to a low-disturbance manure application method, but still wanted to make a good seedbed for planting. A couple of years ago, they began using a strip freshener in the spring where they make strips and plant into those strips. In the fall, the only thing they do is apply manure.

“With the price of fertilizer, we’ve tried to get it over more acres and apply a little less. Then, we do some in-season or preseason nitrogen application to make it go further,” Huntley says. “The manure we haul with tanks that are farther away from the farm gets applied with the rows in strips so we can plant right into that or use a strip freshener if we want to add some. Because we’re putting it on with a tractor and tanks, we could go with the rows.”

Huntley’s hog barns are natural vent so there are no fans or pit fans. The curtains and chimneys open and close to control temperature and air flow. He uses outside storage so the electricity use is minimal. He says the napkin math puts energy use at 20¢ per head. Construction wise, Huntley used cement versus gating as gates would need to be replaced sooner than a cement wall. The No. 1 thing he was thinking about when he made these decisions was cost — not sustainability.

Becoming a more sustainable farming practice starts one decision at a time. Huntley suggests learning on a few acres before transitioning a practice to all of them and remembering it’s a process that takes time; it can’t be done in a year.

Hog manure has played a pivotal role in Josh Nelson's sustainability plan. Photo by Lori Hays.

IT HAS TO MAKE CENTS

Environmental sustainability often leads to financial sustainability. Focusing on soil health, for example, can allow a farmer to cut back on certain purchased inputs or bank nutrients through practices such as no-till and cover crops, Nelson says.

“Partnering that with manure means that very expensive input you just applied to your field will last longer in the soil because you are partnering it with a living root that creates a biological connection that will now provide much more fertility for every crop that comes after,” he adds.

Nelson saves $100-plus an acre by cutting back on nitrogen applications, using cover crops, no-till, smart application methods, and partnering with animal manures and more to improve his soil health.

“Over time, I can cut my herbicide and fertilizer costs. I can stop feeling like I’m on a debt treadmill,” Nelson says. “That’s the side of sustainability people don’t always look at it because some of the things we’re doing in farming aren’t exactly sustainable long term because they’re not financially sustainable. But we’re so worried about next year and the year after, we don’t think about long-term implications.”

Hog manure has played a pivotal role in Nelson’s plan.

“Hog manure was an inexpensive input that woke the soil up and took us from low-producing fields to average fields and now, with a little fine-tuning, it can be high producing. Too many times people treat manure like it’s poop, and it’s not,” Nelson says. “Hog producers are vital to our economy.”

Most of these practices are simple to implement, he adds. No one is asking anyone to go organic and eliminate all synthetic inputs.

“We’re not asking for fundamental changes in the way you farm. A lot of times what we’re saying is: ‘Let’s think of ways to do things more efficiently by partnering with nature,’” Nelson says. “Get rid of that tillage pass ahead of soybeans or put some cover crops down with your manure. Think of ways of implementing some of your nutrient management strategies to get more value out of everything you produce.”

Photo by Josh Nelson.

BUILD A NETWORK

To a certain degree, sustainability is still a “dirty word” in many parts of the country, Nelson says. But it’s an idea a lot of people are coming around to as they start to face the issues of added input costs and more expensive electricity or building materials.

Nelson and Huntley agree they’ve been able to achieve what they have today because they listened to peers and trusted the experience of others. Then, they went for it.

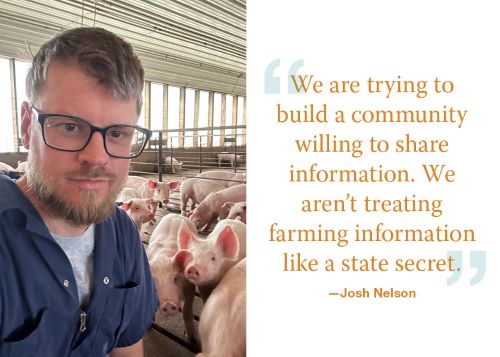

“It used to be you only had your family to ask questions because people were so guarded with their information,” Nelson says. “We are trying to build a community willing to share information. We aren’t treating farming information like a state secret.”

He’s also hired a consultant and built a network of mentors, friends and people with similar goals, who are trying these new practices.

“Anytime I’ve got a question, I love having those people around to ask, ‘What are you doing?’ I work with 60-year-old men who tell me my ideas don’t work, and it’s not coming from a malicious place. They’re not trying to be mean about it or dismissive,” Nelson says. “They’ve been around for a while and have a certain idea of how things should be. It’s a completely different paradigm than how I’m looking at it.”

One of Nelson’s uncles reminded him he’s young enough to mess up and still recover, but he can’t afford a bad year at this stage in the game.

“I’m thinking further down the road, and they’re looking for the exit,” Nelson points out.

In the end, Huntley says all he wants to do is preserve his farm and the environment for future generations.

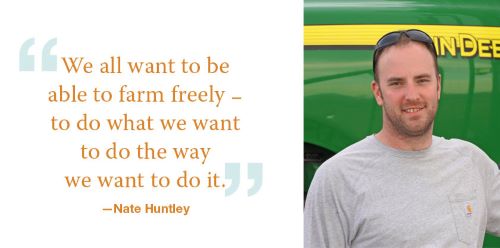

“One of the reasons I want to be an advocate for sustainable farming practices is because we all want to be able to farm freely — to do what we want to do the way we want to do it,” Huntley says.

Read More:

What Holds Farmers Back from Trying New Farming Practices?